Old Santa Barbara Mission Museum, Santa Barbara, California

Creating the 1833 Old Mission Montage

As told from the viewpoint of Jonathan PJ Smith

Jessica Shea from the museum at Old Mission Santa Barbara contacted The Environment Makers about creating a diorama of the Mission as it was in 1833, the year the second bell tower went up and stayed up. The diorama morphed into one large painting depicting the entire Mission complex and seven smaller paintings of the supporting elements, such as the Majordomo’s house and tannery, the orchard, the water system, the Chumash pueblo, etc. The paintings would dimensionally hang from the gallery ceiling to form a surrounding montage of the Mission buildings and grounds as they were in 1833.

Jessica and I started doing the research with the understanding that I’d create quick sketches of our findings. The artist would use these as blueprints for the final paintings.

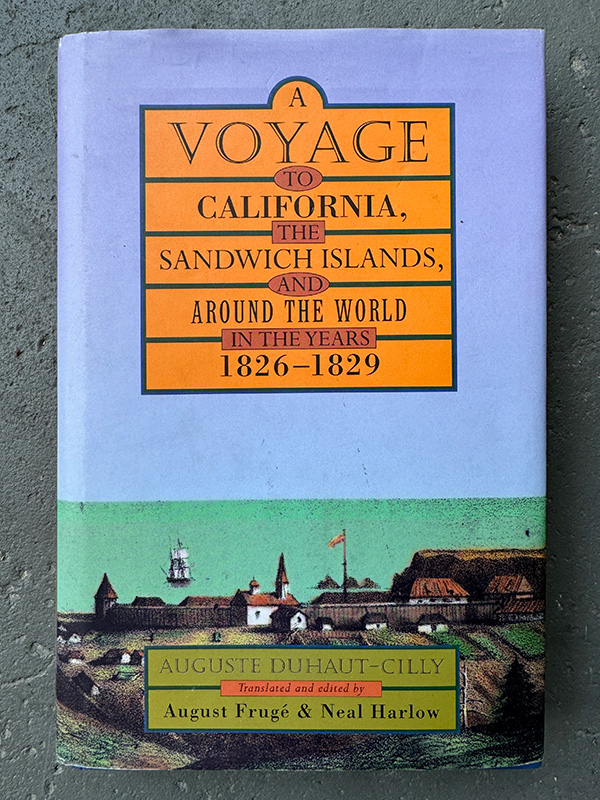

We quickly discovered that information about the early Mission is scant and often contradictory. There were no maps until the mid-1850s, and none of them quite concur. Even the experts we contacted couldn’t supply a complete picture. Through books, particularly those written by foreign travelers in the early 1800’s, we found references and a few meager descriptions. Often, we had to read between the lines to extract kernels of information. The only extant illustrations of the early Mission were made by American travelers in the mid-1800s but often contain peculiar errors and omissions. A measuring device for accuracy became the number of Mission arches the artist drew. The less it had, the more suspect it was. In 1860, someone took the first known photograph. In the 1870s, Santa Barbara photographers Hayward and Muzzall took many more. Despite the 40-year gap from 1833, they proved to be invaluable as they were one of the few sources we could truly rely on. Though most of the original Mission complex is long gone, we walked the grounds to figure out locations and examine the few crumbling remains, like portions of the aqueduct and the pottery. Even now, it is strange to drive past the front of the Mission and know I’m going right through where the Majordomo’s house stood.

Towards the middle of 2023, it became apparent that our artist wouldn’t be able to finish the paintings on time. I’d been using a small iPad and the artist’s app Procreate to create the sketches. In a rash act of bravado, I suggested I could digitally make the images instead. Though they’d be prints, not paintings, Old Mission Santa Barbara agreed on this course of action. I dashed out a one-square-foot image of the gardener’s house as a print sample. It looked good, and I became the official artist. I didn’t know what I was getting myself into and rapidly discovered that I knew little about perspective or the fall of shadows. I’d never even done a proper landscape before. We bought a full-size iPad but this proved to be inadequate. It wasn’t powerful enough to make such large images at print resolution. Instead, I found I had to slice them into manageable pieces and then go back and forth between Procreate and Photoshop to reassemble them.

When it came to depicting details, such as artifacts, tools, and animals, we ran into a field of confusion: what was Mission-era and what wasn’t? We wanted to be accurate but it proved a daunting task. We were, as Jessica put it, world-building. We had to learn about everything, from the types of statues that adorned the façade to how leather was tanned. Through logic and perseverance, we sorted it out, but errors undoubtedly abound.

Month after month, I churned out the pictures, learning as I went and concocting ever more elaborate systems to make the work “easier”. For each of them, Jessica and I put our heads together, poring over and analyzing the information, like two detectives bent on solving a particularly confounding mystery.

When it came time for installation, hanging the images in a level manner proved to be an exercise in invention and frustration all by itself. I think it’s fair to say that, amongst the Mission-Era gnarled beams and decorated plaster walls of the museum gallery, there is not a single straight line or 90-degree angle. Even the tiled floor is like the beginning stretch of a roller coaster. Nonetheless, we prevailed, and the piece is finally up.